Akhenaton is the first person I fell in love with. I copied a line drawing of him embracing Nefertiti, driving on a chariot, while the sun disk god Aten is caressing them with his beautiful little Ankh-hands, onto the wall of my room. I also drew his face in a lot of different styles. I was fourteen years old and so vain to sign these drawings on the back. It enables me today to do exactly what I then thought I should be doing, having passed the old age of forty: to look back in time to my young self that still lives on not only inside me, but on paper, while at the same time has vanished completely as if it had never been.

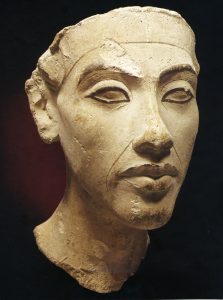

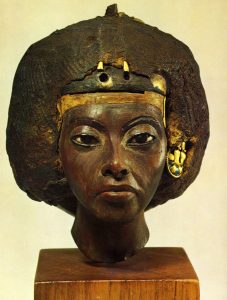

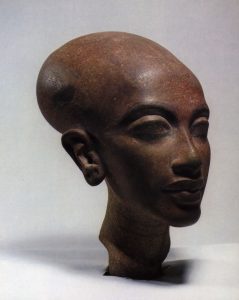

The sculpture I was drawing wasn’t signed, but we know it’s author: the “King’s Favourite and Master of Works” called Thutmose. He made Akhenaton’s features appear almost childlike compared to the elongated caricatures of some years later – rather close to the soft face of his father Amenhotep III – who died as an obese man with dental problems. But the nasolabial folds of his impressive mother Tiye make him easily distinguishable. I learned to recite all the names of this complicated family, and knew their faces apart. When I say I: fell in love, I mean it literally – I felt wasn’t falling in love with an artwork but with a person.

The Egyptians have always been obsessed with survival. They transformed their own living bodies into sculptures, but just to make things safer they also modelled ersatz-bodies to be inhabited by the spirits of the deceased. [1]

Akhenaton, who not only invented a monotheistic sun god that illuminates all living beings and thus brings them to life, also pushed his Master of Works to make artworks that showed all the details of the visible world Aten loved so much – from the chicken pecking it’s way out of the egg to people of different skin colours. [2] As Akhenaton wrote in The Great Hymn to the Aten:

“You alone, shining in your form of living Aten,

Risen, radiant, distant, near.

You made millions of forms from yourself alone,

Towns, villages, fields, the river’s course;

All eyes observe you upon them,

For you are the Aten of daytime on high.”

As long as a person is in the sunlight, she is alive. She was born one day and dies every night until one day she will vanish into the earth and not be visible any more (there won’t be any Osiris to reanimate the soul of the deceased in the underworld).

“When you have dawned they live,

When you set they die;

You yourself are lifetime, one lives by you.

All eyes are on your beauty until you set (…)”[3]

So, immediately it becomes important to show what can be seen, and all things visible are beautiful.

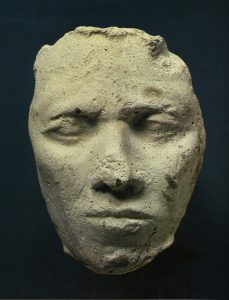

In the short seventeen years reign of Akhenaton (who died around 1336 B.C.), Thutmose attempted different ways to achieve this. He used the sculptural equivalent of photos to create what we today recognize as extremely individual, realist doubles: plaster masks taken from the faces of the important people in court. He then continued working on them, turning them into sculptures that not only mechanically bear the features of a person but seem to be animated by life. The large lips of the small princesses are soft, and almost look as if able to move, talk and kiss.

Nefertiti is not only the eternal beauty most people know but later is shown as an ageing woman. With Akhentaton, the sculptor started by giving him a small belly and was strongly encouraged to not to hold back. Do you see meager arms? Make them look like sticks! Do you think I have woman’s breasts? Well then show them! And do you think I have a weird chin? It is the chin Aten loves!

Last year I finally visited Akhetaton, the city built by Akhenaton. Travel books strongly advise against going to the nearby town of Minya, since there have been Islamist attacks in the 1990s. After we had slipped away from the policeman that had to be paid to be our personal guard we found a very pleasant little town. There’s also the new concrete building destined to house the bust of Nefertiti, if she ever comes home (currently in the collection of the Neues Museum in Berlin).

Akhetaton is next to the Nile. It’s a vast expanse of sand that reflects the sun, surrounded by a fringe of bare cliffs. We asked for the house of Thutmose and were lead to the remains of walls in the sand. The brittle bricks made out of Nile mud dissolve when you touch them. There is no sign and no roof. Our guide poked with one foot in the ground and declared that this was the exact spot where they found the bust of Nefertiti in 1912. This is where Thutmose, the sculptor, lived. He really lived. He is not just an idea of a person. He walked through this door after having talked to Akhenaton. I don’t know what he looked like.